In my final semester at Seton Hall, I enrolled in a relatively new course that focused on Behavioral Finance. I figured it would give me an interesting perspective by drawing connections to psychology and the markets. The course did so much more than just that. It became apparent to me that the concepts that define Behavioral Finance can be pointed out in everyday life, and that the more you learn the more you begin to see it. What also made the course fascinating to me was the fact that we were taught how to read and interpret research papers. Although they may initially seem like they’re written in an entirely different language and are tedious to get through, breaking them down and getting used to the style that they’re written in makes all the difference in taking something away from these readings.

The whole world of Behavioral Finance is a pretty recent idea that has begun gaining credibility because of the way it makes us rethink the way we look at economics/finance. Centuries of neo-classical economics have been built on the premise that people act rationally, but Behavioral Finance argues against that notion. Instead, it assumes that people are predictably irrational. This is the point that Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman, who are often credited as the pioneers of Behavioral Finance/Economics, describe in their paper, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk”(which can be found here: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1914185?seq=1). They found that people tend to exhibit risk-averse behavior when confronted with gains and that they tend to be risk-seeking when confronted with losses.

The rest of this post will describe 3 particular concepts that make up what Behavioral Finance is. It will include research papers and experiments, and I will relate it all to how it affects the broader market.

Loss Aversion

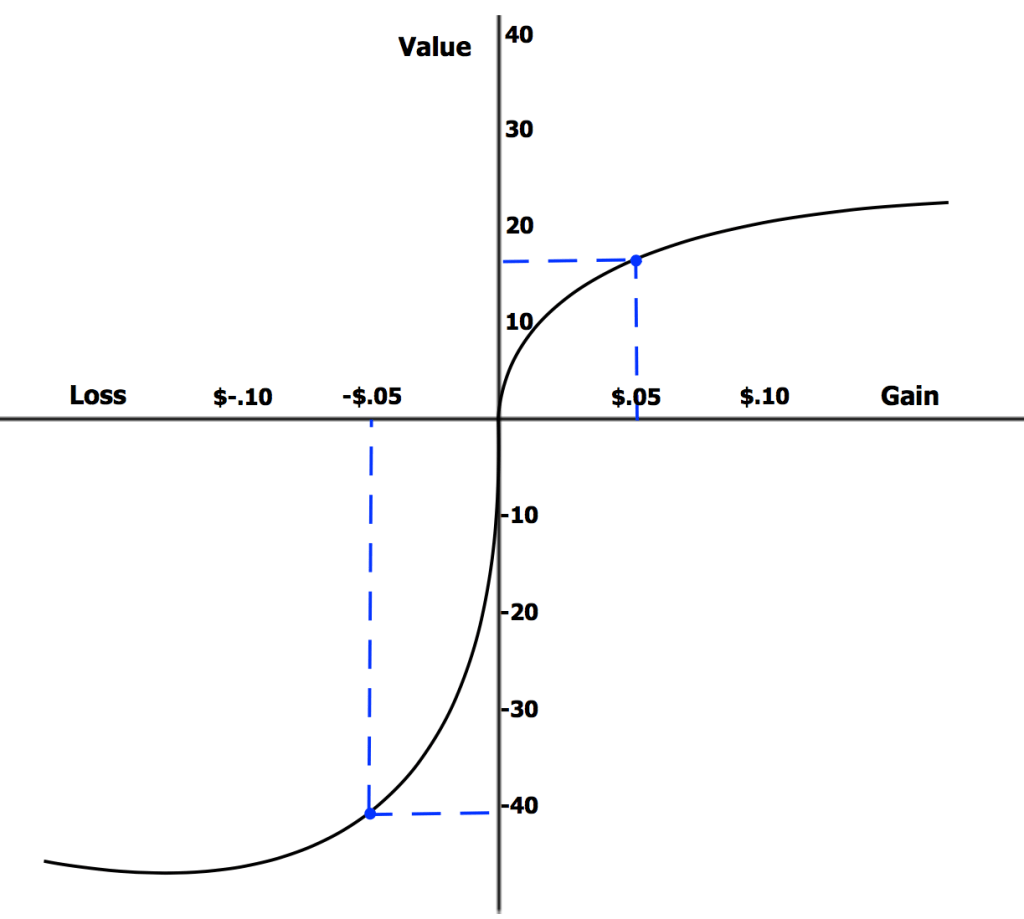

Kahneman and Tversky’s Prospect Theory is based on reference dependence, diminishing sensitivity, probability weighting, and loss aversion. Loss aversion describes how people prefer avoiding losses to acquiring equivalent gains. Essentially, losses feel more than twice as bad as a gain would. In a real-world context, this would be like turning down a full-ride to a top tier university across the country because you don’t want to move away from your family. In that case, you become loss averse to the people you grew up with as that loss would affect you more than gaining an education across the country. There are countless real-world examples of this behavior that you can point out as you go about your day.

From a market perspective, loss aversion can be exhibited when someone sells a stock at a slight gain because they rather take their returns instead of risking the loss of their initial investment. The stock could have gone up higher based on valuation and metrics, but a realized gain of any amount feels much better than a loss. Another example would be holding on to an unrealized gain hoping it will turn into a profit instead of cutting your losses. Loss aversion is a tool that financial advisors, portfolio managers, and bankers can use to understand and mitigate the risks of their investments. It gives them a psychological reason behind the irrationality of how people can behave.

Framing

I find framing to be one of the most interesting concepts because of how prevalent it is. It’s a tool that is used by the media, marketing teams, politicians, sales, and finance among other things. Framing is a cognitive bias that describes the effect presentation has on decision making. This means that people decide on options based on presentation, perception of what the question is trying to say, and personal characteristics. For example, imagine you are presented with 2 choices of meat. One is presented as being 5% fat, and the other 95% lean. Most people are likely to choose the 95% lean meat based on how the choice is framed, despite them being the same thing.

Yoav Ganzach and Nili Karsahi’s paper, “Message Framing and Buying Behavior: A Field Experiment” (which can be found here: http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.317.9267&rep=rep1&type=pdf), puts framing to the test. In the paper, they experimented with loss aversion by partnering with a credit card company. The test consisted of contacting customers who did not use their card for a 3 month period. These customers would receive a communication that either explained what there was to gain from using their card or what would be lost as a result of not using the card. This experiment is in line with the assumptions of both Prospect Theory and Loss Aversion. To sum it up, the results showed that those customers who received the loss-framed communication got twice the credit card utilization and charges compared to those who received the gain-framed message. This experiment shows that when facing a loss, people are more likely to take action and feel the impact of a particular message.

While framing something as a gain may seem to point out enough positives to persuade someone, it is not nearly as strong as framing something as a loss. An M&A banker would be able to use loss aversion and framing to more effectively close deals by emphasizing to clients what they will lose as a result of falling through on a merger. You see it all the time in advertisements, where if you don’t get the latest upgrade or tech, you are falling behind the pack instead of actually gaining something resourceful out of it. It’s this type of power that makes framing one of the most widely used and exhibited cognitive biases.

Endowment Effect

The great part about learning endowment effect in class is that we were unsuspectedly involved in an experiment to prove it ourselves. We participated in a raffle for 7 Behavioral Finance cups. The next week, those who received a cup were asked to put a price on how much they’d sell it for while those who did not get one (the majority of the class) were asked to determine how much they were willing to pay for the cups. The results came out exactly as our Professor had planned. Those who had a glass put a much higher value on it (on average $50) than those who did not (on average $5). This is exactly what the endowment effect is; when people ascribe more value to the things they own. This ties back to loss aversion because of how people want to avoid losing something, so they put a much higher, often unrealistic, value on it.

We have seen 2 big examples of this making financial headlines with the WeWork and Saudi Aramco IPO’s. Both of these cases feature CEO’s and bankers so attached to a company and deal, that they place a much higher value on them than investors are willing to pay for. Understanding this concept puts both of these deals into a better perspective. WeWork was once valued at about $40 billion in the initial stages of the IPO process, but once the bankers started pitching the company’s stock to investors who realized the numbers did not match the value, the deal fell apart in dramatic fashion. In the case of Aramaco, the Saudi leaders in charge of the company got too attached to the idea of having the largest IPO in history and also found it difficult to give up too much stake in the company to foreign investors. Because of this, they drove up the company’s valuation to a point where the bankers working on the deal have struggled to justify the $2 trillion figure Aramco had in mind.

In conclusion…

Behavioral Finance helps us put financial decision making into a psychological context by explaining the patterns in which humans behave irrationally. It has been a pleasure having taken this course because of how fascinating it is to tie these concepts back to everyday life and finance. What makes it so exciting is how young the field of Behavioral Finance is. Over time, it will continue to develop in order to help investors and financial professionals make more well-informed decisions while gaining better risk-adjusted returns.

-S.F.

References

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk.” Econometrica, vol. 47, no. 2, 1979, pp. 263–291. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/1914185.

Ganzach, Yoav, and Nili Karsahi. “Message Framing and Buying Behavior: A Field Experiment.” Journal of Business Research, vol. 32, no. 1, 1995, pp. 11–17., doi:10.1016/0148-2963(93)00038-3.