Interest rate derivatives make up some of the most complex, yet essential products in the financial system. They help lenders reshape and transform their risk while lowering financing costs and improving access to capital for borrowers. Two of the most general interest rate derivatives are interest rate swaps and forward rate agreements. These products are unique in that the underlying asset is an interest rate rather than a given security or commodity. Their use cases include balance sheet management, hedging against interest rate movements/uncertainty in the markets, and speculation. In this article, I’ll explore the differences between the two instruments, their risk and return characteristics, and outline the role they play in our financial markets.

Interest Rate Swaps

In essence, an interest rate swap is an agreement between two parties in which a series of periodic payments are exchanged over a given amount of time. These payments are netted at each settlement date with only one party making a net payment and the other receiving the difference. For instance, if on a given settlement date party A has a fixed liability of $60 and party B has a floating liability of $80, then party B will make a net payment of $20 to party A. Whichever party has the greater liability on the settlement date will be the one required to make the net payment to the other party. The value of each payment on the settlement date is derived from the rate on a notional principal amount which is never actually exchanged throughout the life of the contract. Since swaps are traded in over-the-counter markets, these contracts are bespoke and tailored to each party’s agreed upon terms.

The example in the prior paragraph describes a plain vanilla swap. This type of swap contract implies a fixed-for-floating rate exchange and is the simplest variation of a swap. Other types of swaps include basis swaps, which describes trading a floating rate for another floating rate. The universe of swaps however is vast and beyond the scope of this article, so I will focus on the plain vanilla interest rate swap.

Forward Rate Agreements

This type of interest rate derivative is based on a standard forward contract in which two parties agree to exchange an asset on a given date in the future for a price locked in at the initiation of the trade. In a forward rate agreement (FRA), the underlying asset is a future interest rate on a notional principal amount, which is never exchanged. Cash-settlement of the contract is based on the net difference between the contract’s interest rate and a reference rate. The most commonly used underlying rate in an FRA is LIBOR (which is in the process of being phased out in deference to a new rate, SOFR). Since an FRA is essentially locking in a rate for a future date, it is a valuable hedge to future borrowing/lending risk as it allows firms to have a clearer outlook on their liabilities. For example, a firm that anticipates a need to borrow money in 30 days could initiate a long FRA position. If the future 90-day rate (usually LIBOR) increases, the firm will receive a payment. If the future 90-day rate decreases, the firm will instead have to make a payment. If perfectly hedged, the firm’s cost of borrowing will not be higher, nor lower despite increases or decreases in the reference rate.

FRAs also trade over-the-counter and are highly customizable. Depending on the circumstances, a synthetic FRA can be constructed by using two LIBOR loans to replicate an FRAs payment structure.

What’s the difference?

Given the brief description of both products above, it seems as though they are very similar in nature. They both derive payments from a notional principal amount that is never exchanged, trade over-the-counter and are custom, use interest rates as the underlying, and are subject to default risk among many other shared qualities. They are also both primarily used by large institutions and professional traders.

The major difference that sets them apart is the payment structure. An interest rate swap involves a series of netted cash flows involving two parties, whereas an FRA is structured as a single net cashflow paid from one party to the other. This creates an interesting circumstance because given these two structures, an interest rate swap could be replicated using a series of FRAs.

Risks

Like many derivative transactions, interest rate swaps can become tricky to unwind when the position moves against a firm’s initial expectations. Harvard University’s plans to finance expansion in 2004 present a great example of an expensive exit from swap transactions. The university’s endowment found itself in a favorable financial position at the time; the fund had returned 16% annually over the past decade and its assets were valued at $22.6 billion. Hoping to capitalize on its strength and keep momentum moving forward, the university made plans to borrow $1.8 billion in 2008 with an additional $500 million planned through to 2020. In order to hedge the future debt issues and lock in historically low financing costs (the US Federal Reserve’s overnight rate was 2.25% at the time), Harvard entered into $2.3 billion worth of interest rate swaps. Things took a turn for the university in 2008 however when the credit crisis caused central banks to lower rates, which led to huge losses on the swaps since they’d be paying a premium over market rates. This saw the value of their endowment fund, which had grown to as high as $36 billion, fall 30% to $26 billion, triggering a liquidity crisis.

In an effort to unwind the position in interest rate swaps, the university had to issue debt to terminate $1.1 billion worth of the swaps with the remaining amount to be paid over 30+ years. This led to considerable cost-cutting initiatives around campus at a time when they were supposed to be expanding. The Harvard deal really illustrates how you can have the right idea (it made sense to lock in what they thought were low rates at the time), but still get burned by derivatives when markets don’t move as originally forecasted.

Conclusion

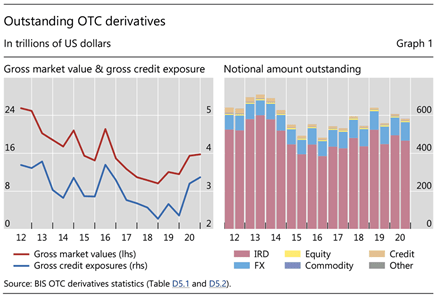

According to the Bank for International Settlements, the gross market value of over-the-counter derivatives increased to $15.8 trillion during the 2nd half of 2020. The total notional amount of these derivatives came in at $582 trillion, of which interest rate derivatives made up just over 80% at $467 trillion.

Interest rate derivatives are embedded into all corners of the financial system as more firms and institutions rely on these instruments to reshape risk and hedge against uncertainty. They are fascinating tools to try to understand, especially as they get more complex, with interest rate swaps and FRAs serving as a nice introduction to the topic. Financial innovation will continue to find clever ways to repackage risk and make the landscape for derivatives even more expansive than it currently stands.